QUALITY, RELIABILITY, SAFETY AND CYBERSECURITY

Modern technologies and new digitised services are key to ensuring the stable growth and development of the European Union and its society. These new technologies are largely based on smart electronic components and systems (ECS). Highly automated or autonomous transportation systems, improved healthcare, industrial production, information and communication networks, and energy grids all depend on the availability of electronic systems. The main societal functions1 and critical infrastructure are governed by the efficient accessibility of smart systems and the uninterrupted availability of services.

Ensuring the reliability, safety and security of ECS is a Major Challenge since the simultaneous demand for increased functionality and continuous miniaturisation of electronic components and systems causes interactions on multiple levels. A degraded behaviour in any of these dimensions (quality, reliability, safety, and security) or an incorrect integration among them, would affect vital properties and could cause serious damage. In addition, such shortcomings in safety, reliability and security might even outweigh the societal and individual benefits perceived by users, thus lowering trust in, and acceptance of, the technologies.

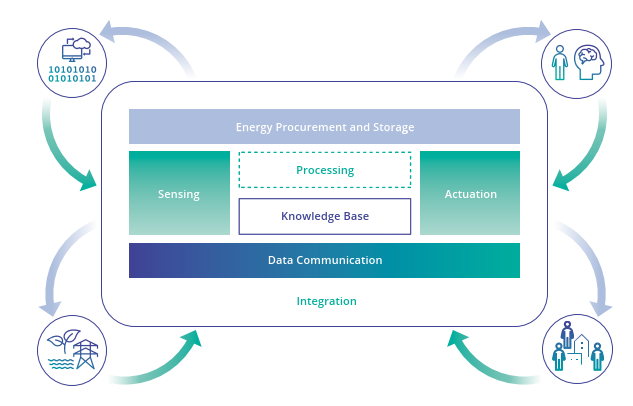

These topics and features constitute the core of this Chapter, which addresses these complex interdependencies by considering input from, and necessary interaction between, major disciplines. Moreover, quality, reliability, safety and cybersecurity of electronic components and systems are, and will be, fundamental to digitised society (see Figure 2.4.1). In addition, the tremendous increase of computational power and reduced communication latency of components and systems, coupled with hybrid and distributed architectures, impose to rethink many “traditional” approaches and expected performances towards safety and security, exploiting AI and ML (machine learning).

In practice, ensuring reliability, safety, and security of ECS is part of the Design, Implementation, and Validation/Testing process of the respective manufacturers and – for reasons of complexity and diversity/heterogeneity of the systems – must be supported by (analysing and testing) tools. Thus, the techniques described in Chapter 2.3 (Architecture and Design: Method and Tools) are complementary to the techniques presented here: in that Chapter, corresponding challenges are described from the design process viewpoint, whereas here we focus on a detailed description of the challenges concerning reliability, safety, and security within the levels of the design hierarchy.

Figure 2.4.1 - Role of quality, reliability, safety and cybersecurity of electronic components and systems for digitalisation.

To introduce the topic presented in this Chapter, we first present some definitions that will be useful to clarify the concepts described in the Major Challenges.

Production quality: often defined as “the ability of a system being suitable for its intended purpose while satisfying customer expectations”, this is a very broad definition that basically includes everything. Another widely used definition is “the degree a product meets requirements in specifications” – but without defining the underlying specifications, the interpretation can vary a lot between different stakeholders. Therefore, in this Chapter quality will be defined “as the degree to which a product meets requirements in specifications that regulate how the product should be designed and manufactured, including environmental stress screening (such as burn-in) but no other type of testing”. In this way, reliability, dependability and cybersecurity, which for some would be expected to be included under quality, will be treated separately.

Reliability: this is the ability or the probability, respectively, of a system or component to function as specified under stated conditions for a specified time.

Prognostics and health management: a method that permits the assessment of the reliability of the product (or system) under its application conditions.

Functional safety: the ability of a system or piece of equipment to control recognized hazards to achieve an acceptable level of risk, such as to maintain the required minimum level of operation even in the case of likely operator errors, hardware failures and environmental changes to prevent physical injuries or damages to the health of people, either directly or indirectly.

Dependability: according to IEC 60050-192:2015, dependability (192-01-22) is the ability of an item to perform as and when required. An item here (192-01-01) can be an individual part, component, device, functional unit, equipment, subsystem or system. Dependability includes availability (192-01-23), reliability (192-01-24), recoverability (192-01-25), maintainability (192-01- 27) and maintenance support performance (192-01-29), and in some cases other characteristics such as durability (192-01-21), safety and security. A more extensive description of dependability is available from the IEC technical committee on dependability (IEC TC 56).

Safety: freedom from unacceptable risk of harm [CENELEC 50126].

Security: measures can provide controls relating to physical security (control of physical access to computing assets) or logical security (capability to login to a given system and application) (IEC 62443-1-1):

measures taken to protect a system;

condition of a system that results from the establishment and maintenance of measures to protect the system;

condition of system resources being free from unauthorized access, and from unauthorized or accidental change, destruction or loss;

capability of a computer-based system to provide adequate confidence that unauthorized persons and systems can neither modify the software and its data nor gain access to the system functions, and yet ensure that this is not denied to authorized persons and systems;

prevention of illegal or unwanted penetration of, or interference with, the proper and intended operation of an industrial automation and control system.

Cybersecurity: the protection of information against unauthorized disclosure, transfer, modification or destruction, whether accidental or intentional (IEC 62351-2).

Robust root of trust systems: these are based on cryptographic functionalities that ensure the authenticity and integrity of the hardware and software components of the system, with assurance that it is resilient to logical and physical attacks.

Emulation and Forecasting: cybersecurity evolution in parallel to increasing computation power and hybrid threats mixing geopolitical, climate change and any other external threats impose to anticipate the horizon of resilience, safety and security of systems forecasting attacks and incidents fast evolution.

Five Major Challenges have been identified:

Major Challenge 1: ensuring HW quality and reliability.

Major Challenge 2: ensuring dependability in connected software.

Major Challenge 3: ensuring cyber-security and privacy.

Major Challenge 4: ensuring of safety and resilience.

Major Challenge 5: human systems integration.

With the ever-increasing complexity and demand for higher functionality of electronics, while at the same time meeting the demands of cutting costs, lower levels of power consumption and miniaturization in integration, hardware development cannot be decoupled from software development. Specifically, when assuring reliability, separate hardware development and testing according to the second-generation reliability methodology (design for reliability, DfR) is not sufficient to ensure the reliable function of the ECS. A third-generation reliability methodology must be introduced to meet these challenges. For the electronic smart systems used in future highly automated and autonomous systems, a next generation of reliability is therefore required. This new generation of reliability assessment will introduce in situ monitoring of the state of health on both a local (e.g. IC packaging) and system level. Hybrid prognostic and health management (PHM) supported by Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the key methodology here. This marks the main difference between the second and the third generation. DfR concerns the total lifetime of a full population of systems under anticipated service conditions and its statistical characterization. PHM, on the other hand, considers the degradation of the individual system in its actual service conditions and the estimation of its specific remaining useful life (RUL).

Since embedded systems control so many processes, the increased complexity by itself is a reliability challenge. Growing complexity makes it more difficult to foresee all dependencies during design. It is impossible to test all variations, and user interfaces need greater scrutiny since they have to handle such complexity without confusing the user or generating uncertainties.

The trend towards interconnected, highly automated and autonomous systems will change the way we own products. Instead of buying commodity products, we will instead purchase personalized services. The vision of Major challenge 1 is to provide the requisite tools and methods for novel ECS solutions to meet ever- increasing product requirements and provide availability of ECS during use in the field. Therefore, availability will be the major feature of ECS. Both the continuous improvement of existing methods (e.g. DfR) and development of the new techniques (PHM) will be the cornerstone of future developments in ECS (see also Challenges 1 and 2, and especially the key focus areas on lifecycle-aware holistic design flows in Chapter 2.3 Architecture and Design: Methods and Tools). The main focus of Major challenge 1 will circulate around the following topics.

Digitization, by improving collaboration within the supply chain to introduce complex ECS earlier in the market.

Continuous improvement of the DfR methodology through simultaneous miniaturization and increasing complexity.

Model-based design is a main driver of decreasing time-to-market and reducing the cost of products.

Availability of the ECS for highly automated and autonomous systems will be successfully introduced in the market based on PHM.

Data science and AI will drive technology development and pave the way for PHM implementation for ECS.

AI and PHM based risk management.

Inline inspection and highly accelerated testing methods for quality and robustness monitoring during production of ECS with ever-increasing complexity and heterogeneity for demanding applications should increase the yield and reduce the rate of early fails (failures immediately following the start of the use period).

Controlling, beyond traditional approaches, the process parameters in the era of Industry 4.0 to minimize deviations and improve quality of key performance indicators (KPIs).

Process and materials variabilities will have to be characterized to quantify their effects on hardware reliability, using a combination of empirical studies, fundamental RP models and AI approaches.

Advanced/smart monitoring of process output (e.g. measuring the 3D profile of assembled goods) for the detection of abnormities (using AI for the early detection of standard outputs).

Early detection of potential yield/reliability issues by simulation-assisted design for assembly/design for manufacturing (DfM/DfA) as a part of virtual prototyping.

Digitization is not possible without processing and exchange data between partners.

Involving European stakeholders to resolve the issue of data ownership:

Create best practices and scalable workflows for sharing data across the supply chain while maintaining intellectual property (IP).

Standardize the data exchange format, procedures and ownership, and create an international legal framework.

Conceive and validate business models creating economic incentives and facilitating sharing data, and machine learning algorithms dealing with data.

Handling and interpreting big data:

Realise consistent data collection and ground truth generation via annotation/labelling of relevant events.

Create and validate a usable and time-efficient workflow for supervised learning.

Standardized model training and model testing process.

Standardized procedures for model maintenance and upgrade.

Make a link between data from Industry 4.0 and model-based engineering:

Derive working hypotheses about system health.

Validate hypothesis and refine physics-based models.

Construct data models-based embedding (new) domain knowledge derived from model-based engineering.

Identify significant parameters that must be saved during production to be re-used later for field-related events, and vice versa – i.e. feed important insights derived from field data (product usage monitoring) into design and production. This is also mandatory to comply with data protection laws.

Evaluate methods for the indirect characterization of ECS using end-of-line test data.

Wafer fabrication (pre-assembly) inline and offline tests for electronics, sensors and actuators, and complex hardware (e.g. multicore, graphics processing unit, GPU) that also cover interaction effects such as heterogeneous 3D integration and packaging approaches for advanced technologies nodes (e.g. thin dice for power application – dicing and grinding).

Continuous improvement of physics of failure (PoF) based methodologies combined with new data-driven approaches: tests, analyses and degradation, and lifetime models (including their possible reconfiguration):

Identifying and adapting methodology to the main technology drivers.

Methods and equipment for dedicated third-level reliability assessments (first level: component; second level: board; third level: system with its housing, e.g. massive metal box), as well as accounting for the interactions between the hierarchy levels (element, device, component, sub-module, module, system, application).

Comprehensive understanding of failure mechanisms, lifetime prediction models (including multi-loading conditions), continuously updating for new failure mechanisms related to innovative technologies (advanced complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS), µ-fluidics, optical input/output (I/O), 3D printing, wide bandgap technologies, etc). New materials and production processes (e.g. 3D printing, wide bandgap technologies, etc), and new interdisciplinary system approaches and system integration technologies (e.g. µ-fluidics, optical input/output (I/O), etc).

Accelerated testing methods (e.g. high temperature, high power applications) based on mission profiles and failure data (from field use and tests):

Use field data to derive hypotheses that enable improved prioritization and design of testing.

Usage of field, PHM and test data to build models for ECS working at the limit of the technology as accelerating testing is limited.

Standardize the format of mission profiles and the procedure on how mission profiles are deducted from multimodal loading.

Design to field – better understanding of field conditions through standardized methodology over supply chain using field load simulator.

Understanding and handling of new, unforeseen and unintended use conditions for automated and autonomous systems.

Embedded reliability monitoring (pre-warning of deterioration) with intelligent feedback towards autonomous system(s).

Identification of the 10 most relevant field-related failure modes based on integrated mission profile sensors.

Methods to screen out weak components with machine learning (ML) based on a combination of many measured parameters or built-in sensor data.

New standards/methodologies/paradigms that evaluate the “ultimate” strength of systems – i.e. no longer test whether a certain number of cycles are “pass”, but go for the limit to identify the actual safety margin of systems, and additionally the behavior of damaged systems, so that AI can search for these damage patterns.

Digital twin software development for reliability analysis of assets/machines, etc.

Comprehensive understanding of the SW influence on HW reliability and its interaction:

SW Reliability: start using maturity growth modelling techniques, develop models and gather model parameters.

SW/HW Reliability modelling: find ways as to combine the modelling techniques (in other words: scrunch the different time domains).

SW/HW Reliability testing: find ways as to test systems with software and find the interaction failure modes.

Approaches for exchanging digital twin models along the supply chain while protecting sensitive partner IP and adaptation of novel standard reliability procedures across the supply chain.

Digital twin as main driver of robust ECS system:

Identifying main technology enablers.

Development of infrastructure required for safe and secure information flow.

Development of compact PoF models at the component and system level that can be executed in situ at the system level – metamodels as the basis of digital twins.

Training and validation strategies for digital twins.

Digital twin-based asset/machine condition prediction.

Electronic design automation (EDA) tools to bridge the different scales and domains by integrating a virtual design flow.

Virtual design of experiment as a best practice at the early design stage.

Realistic material and interface characterization depending on actual dimensions, fabrication process conditions, ageing effects, etc., covering all critical structures, generating strength data of interfaces with statistical distribution.

Mathematical reliability models that also account for the interdependencies between the hierarchy levels (device, component, system).

Mathematical modelling of competing and/or superimposed failure modes.

New model-based reliability assessment in the era of automated systems.

Development of fully harmonized methods and tools for model-based engineering across the supply chain:

Material characterization and modelling, including effects of ageing.

Multi-domain physics of failure simulations.

Reduced modelling (compact models, metamodels, etc.).

Failure criteria for dominant failure modes.

Verification and validation techniques.

Standardization as a tool for model-based development of ECS across the supply chain:

Standardization of material characterization and modelling, including effects of ageing.

Standardization of simulation-driven design for excellence (DfX).

Standardization of model exchange format within supply chain using functional mock-up unit (FMU) and functional mock-up interface (FMI) (and also components).

Simulation data and process management.

Initiate and drive standardization process for above-mentioned points.

Extend common design and process failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) with reliability risk assessment features (“reliability FMEA”).

Generic simulation flow for virtual testing under accelerated and operational conditions (virtual “pass/fail” approach).

Automation of model build-up (databases of components, materials).

Use of AI in model parametrization/identification, e.g. extracting material models from measurement.

Virtual release of ECS through referencing.

Self-monitoring, self-assessment and resilience concepts for automated and autonomous systems based on the merger of PoF, data science and ML for safe failure prevention through timely predictive maintenance.

Self-diagnostic tools and robust control algorithms validated by physical fault-injection techniques (e.g. by using end-of-life (EOL) components).

Hierarchical and scalable health management architectures and platforms, integrating diagnostic and prognostic capabilities, from components to complete systems.

Standardized protocols and interfaces for PHM facilitating deployment and exploitation.

Monitoring test structures and/or monitor procedures on the component and module levels for monitoring temperatures, operating modes, parameter drifts, interconnect degradation, etc.

Identification of early warning failure indicators and the development of methods for predicting the remaining useful life of the practical system in its use conditions.

Development of schemes and tools using ML techniques and AI for PHM.

Implementation of resilient procedures for safety-critical applications.

Big sensor data management (data fusion, find correlations, secure communication), legal framework between companies and countries).

Distributed data collection, model construction, model update and maintenance.

Concept of digital twin: provide quality and reliability metrics (key failure indicator, KFI).

Using PHM methodology for accelerated testing methods and techniques.

Development of AI-supported failure diagnostic and repair processes for improve field data quality.

AI-based asset/machine/robot life extension method development based on PHM.

AI-based autonomous testing tool for verification and validation (V&V) of software reliability.

Lifecycle management – modeling of the cost of the lifecycle.

Connected software applications such as those used on the Internet of Things (IoT) differ significantly in their software architecture from traditional reliable software used in industrial applications. The design of connected IoT software is based on traditional protocols originally designed for data communications for PCs accessing the internet. This includes protocols such as transmission control protocol/internet protocol (TCP/IP), the re-use of software from the IT world, including protocol stacks, web servers and the like. This also means the employed software components are not designed with dependability in mind, as there is typically no redundancy and little arrangements for availability. If something does not work, end-users are used to restarting the device. Even if it does not happen very often, this degree of availability is not sufficient for critical functionalities, and redundancy hardware and back-up plans in ICT infrastructure and network outages still continue to occur. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that we design future connected software that is conceived either in a dependable way or can react reliably in the case of infrastructure failures to achieve higher software quality.

The vision is that networked systems will become as dependable and predictable for end-users as traditional industrial applications interconnected via dedicated signal lines. This means that the employed connected software components, architectures and technologies will have to be enriched to deal with dependability for their operation. Future dependable connected software will also be able to detect in advance if network conditions change – e.g. due to foreseeable transmission bottlenecks or planned maintenance measures. If outages do happen, the user or end application should receive clear feedback on how long the problem will last so they can take potential measures. In addition, the consideration of redundancy in the software architecture must be considered for critical applications. The availability of a European ecosystem for reliable software components will also reduce the dependence on current ICT technologies from the US and China.

In the past, reliable and dependable software was always directly deployed on specialised, reliable hardware. However, with the increased use of IoT, edge and cloud computing, critical software functions will also be used that are completely decoupled from the location of use (e.g. in use cases where the police want to stop self-driving cars from a distance):

Software reliability in the face of infrastructure instability.

Dependable edge and cloud computing, including dependable and reliable AI/ML methods and algorithms.

Dependable communication methods, protocols and infrastructure.

Formal verification of protocols and mechanisms, including those using AI/ML.

Monitoring, detection and mitigation of security issues on communication protocols.

Quantum key distribution (“quantum cryptography”).

Increasing software quality by AI-assisted development and testing methods.

Infrastructure resilience and adaptability to new threats.

Secure and reliable over-the-air (OTA) updates.

Using AI for autonomy, network behaviour and self-adaptivity.

Dependable integration platforms.

Dependable cooperation of System of Systems (SoS).

This Major Challenge is tightly interlinked with the cross-sectional technology of 2.2 Connectivity Chapter, where the focus is on innovative connectivity technologies. The dependability aspect covered within this challenge is complementary to that chapter since dependability and reliability approaches can also be used for systems without connectivity.

Figure 2.4.2 - Software-defined networking (SDN) market size by 2025 (Source: Global Markets Insight, Report ID GMI2395, 2018)

Changing or updating software by retaining existing hardware is quite common in many industrial domains. However, keeping existing reliable software and changing the underlying hardware is difficult, especially for critical applications. By decoupling software functionalities from the underlying hardware, softwarisation and virtualisation are two disruptive paradigms that can bring enormous flexibility and thus promote strong growth in the market (see Figure 2.4.2). However, the softwarisation of network functions raises reliability concerns, as they will be exposed to faults in commodity hardware and software components:

Software-defined radio (SDR) technology for highly reliable wireless communications with higher immunity to cyber-attacks.

Network functions virtualisation infrastructure (NFVI) reliability.

Reliable containerisation technologies.

Resilient multi-tenancy environments.

AI-based autonomous testing for V&V of software reliability, including the software-in-the-loop (SiL) approach.

Testing tools and frameworks for V&V of AI/ML-based software reliability, including the SiL approach.

Unlike hardware failures, software systems do not degrade over time unless modified. The most effective approach for achieving higher software reliability is to reduce the likelihood of latent defects in the released software. Mathematical functions that describe fault detection and removal phenomenon in software have begun to emerge. These software reliability growth models (SRGM), in combination with Bayesian statistics, need further attention within the hardware-orientated reliability community over the coming years:

HW failure modes are considered in the software requirements definition.

Design characteristics will not cause the software to overstress the HW, or adversely change failure-severity consequences on the occurrence of failure.

Establish techniques that can combine SW reliability metrics with HW reliability metrics.

Develop efficient (hierarchical) test strategies for combined SW/HW performance of connected products.

Dependability in connected software is strongly connected with other chapters in this document. In particular, additional challenges are handled in following chapters:

Chapter 1.3 Embedded Software and Beyond: Major Challenge 1 (MC1) efficient engineering of software; MC2 continuous integration of embedded software; MC3 lifecycle management of embedded software; and MC6 Embedding reliability and trust.

Chapter 1.4 System of Systems: MC1 SoS architecture; MC4 Systems of embedded and cyber-physical systems engineering; and MC5 Open system of embedded and cyber-physical systems platforms.

Chapter 2.1 Edge Computing and Embedded Artificial Intelligence: MC1: Increasing the energy efficiency of computing systems.

Chapter 2.2 Connectivity: MC4: Architectures and reference implementations of interoperable, secure, scalable, smart and evolvable IoT and SoS connectivity.

Chapter 2.3 Architecture and Design: Method and Tools: MC3: Managing complexity.

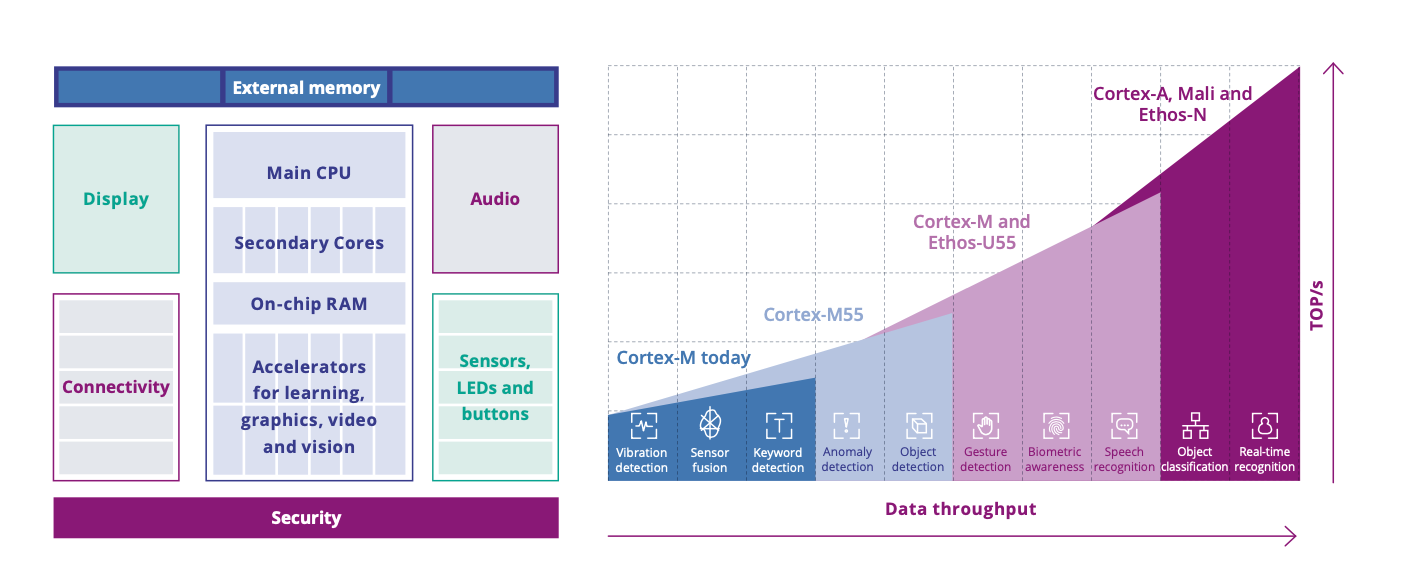

We have witnessed a massive increase in pervasive and potentially connected digital products in our personal, social and professional spheres, enhanced by new features of 5G networks and beyond. Connectivity provides better flexibility and usability of these products in different sectors, with a tremendous growth of sensitive and valuable data. Moreover, the variety of deployments and configuration options and the growing number of sub-systems changing in dynamicity and variability increase the overall complexity. In this scenario, new security and privacy issues have to be addressed, also considering the continuously evolving threat landscape. New approaches, methodologies and tools for risk and vulnerability analysis, threat modeling for security and privacy, threat information sharing and reasoning are required. Artificial intelligence (e.g., machine learning, deep learning and ontology) not only promotes pervasive intelligence supporting daily life, industrial developments, personalisation of mass products around individual preferences and requirements, efficient and smart interaction among IoT in any type of services, but It also fosters automation, to mitigate such complexity and avoid human mistakes.

Embedded and distributed AI functionality is growing at speed in both (connected) devices and services. AI-capable chips will also enable edge applications allowing decisions to be made locally at device level. Therefore, resilience to cyber-attacks is of utmost importance. AI can have a direct action on the behaviour of a device, possibly impacting its physical life inducing potential safety concerns. AI systems rely on software and hardware that can be embedded in components, but also on the set of data generated and used to make decisions. Cyber-attacks, such as data poisoning or adversarial inputs, could cause physical harm and/or also violate privacy. The development of AI should therefore go hand in hand with frameworks that assess security and safety to guarantee that AI systems developed for the EU market are safe to use, trustworthy, reliable and remain under control (C.f. Chapter 1.3 “Embedded Software and beyond” for quality of AI used in embedded software when being considered as a technology interacting with other software components).

The combination of composed digital products and AI highlights the importance of trustable systems that weave together privacy and cybersecurity with safety and resilience. Automated vehicles, for example, are adopting an ever-expanding combination of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) developed to increase the level of safety, driving comfort exploiting different type of sensors, devices and on-board computers (sensors, Global Positioning System (GPS), radar, lidar, cameras, on-board computers, etc.). To complement ADAS systems, Vehicle to X (V2X) communication technologies are gaining momentum. Cellular based V2X communication provides the ability for vehicles to communicate with other vehicle and infrastructure and environment around them, exchanging both basic safety messages to avoid collisions and, according to the 5g standard evolutions, also high throughput sensor sharing, intent trajectory sharing, coordinated driving and autonomous driving. The connected autonomous vehicle scenarios offer many advantages in terms of safety, fuel consumption and CO2 emissions reduction, but the increased connectivity, number of devices and automation, expose those systems to several crucial cyber and privacy threats, which must be addressed and mitigated.

Autonomous vehicles represent a truly disruptive innovation for travelling and transportation, and should be able to warrant confidentiality of the driver’s and vehicle’s information. Those vehicles should also avoid obstacles, identify failures (if any) and mitigate them, as well as prevent cyber-attacks while staying safely operational (at reduced functionality) either through human-initiated intervention, by automatic inside action or remotely by law enforcement in the case of any failure, security breach, sudden obstacle, crash, etc.

In the evoked scenario the main cybersecurity and privacy challenges deal with:

Interoperable security and privacy management in heterogeneous systems including cyber-physical systems, IoT, virtual technologies, clouds, communication networks, autonomous systems.

Real time monitoring and privacy and security risk assessment to manage the dynamicity and variability of systems.

Developing novel privacy preserving identity management and secure cryptographic solutions.

Novel approaches to hardware security vulnerabilities and other system weaknesses as - for instance – Spectre and Meltdown or side channel attacks (c.f. appendix A).

Developing new approaches, methodologies and tools empowered by AI in all its declinations (e.g. machine learning, deep learning, ontology).

Investigating a deep verification approach towards also open-source hardware in synergy and implementing the security by-design paradigm (c.f. appendix A).

Investigating the interworking among safety, cybersecurity, trustworthiness, privacy and legal compliance of systems.

Evaluating the impact in term of sustainability and green deal of the adopted solutions.

The cornerstone of our vision rests on the following four pillars. First, a robust root of trust system, with unique identification enabling security without interruption from the hardware level right up to the applications, including AI, involved in the accomplishment of the system’s mission in dynamic unknown environments. This aspect has a tremendous impact on mission critical systems with lots of reliability, quality and safety & security concerns. Second, protection of the EU citizen’s privacy and security while at the same keeping usability levels and operation in a competitive market where also industrial Intellectual Protection should be considered. Third, the proposed technical solutions should contribute to the green deal ambition, for example by reducing their environmental impact. Finally, proof-of-concept demonstrators that are capable of simultaneously guaranteeing (a given level of) security and (a given level of) privacy, as well as potentially evolving in-reference designs that illustrate how practical solutions can be implemented (i.e. thereby providing guidelines to re-use or adapt).

End to end encryption of data, both in transit and at rest is kept to effectively protect privacy and security. The advent of quantum computing technology introduces new risks and threats, since attacks using quantum computing may affect traditional cryptographic mechanisms. New quantum safe cryptography is required, referring both to quantum cryptography and post quantum cryptography with standard crypto primitives.

Also, the roadmap for Open Source HW/SW & RISC-V IP blocks will open the path to domain-focused processors or domain-specific architectures (for instance, but not limited to the “chiplet-based approach”), which may lead to new approaches to cybersecurity and safety functions or implementation as well as new challenges and vulnerabilities that must be analysed (c.f. Appendix A).

Putting together seamlessly security and privacy requirements is a difficult challenge that also involves some non-technical aspects. The human factor can often cause security and privacy concerns, despite of technologically advanced tools and solutions. Another aspect relates to security certification versus certification cost. A certification security that does not mitigate the risks and threats, increases costs with minimal benefits. Therefore, all techniques and methodology to reduce such a cost are in the scope of the challenge.

In light of this scenario, this Major Challenge aims at contributing to the European strategic autonomy plan in terms of cybersecurity, digital trustworthiness and the protection of personal data.

Digital Trust is mandatory in a global scenario, based on ever-increasing connectivity, data and advanced technologies. Trustworthiness is a high-level concern including not only privacy and security issues, but also safety and resilience and reliability. The goal is a robust, secure, and privacy preserving system that operates in a complex ecosystem without interruption, from the hardware level up to applications, including systems that may be AI-enabled. This challenge calls for a multidisciplinary approach, spanning across technologies, regulations, compliance, legal and economic issues. To this end, the main expected outcomes can be defined as:

Defining different methods and techniques of trust for a system, and proving compliance to a security standard via certification schemes.

Defining methods and techniques to ensure trustworthiness of AI algorithms, included explainable (XAI) (cfr. Chapter 2.1 “Edge Computing and Embedded Artificial Intelligence”)

Developing methodologies and techniques from hardware trustworthy to software layers trustworthy (cfr. Chapter 1.3 “Embedded Software and Beyond” and Chapter 1.4 “System of Systems”).

Defining methods and tools to support the composition and validation of certified parts addressing multiple standards (cfr. Chapter 1.4 “System of Systems” and Chapter 2.3 “Architecture and Design: Methods and Tools”).

Definition and future consolidation of a framework providing guidelines, good practices and standards oriented to trust.

Enhancing current tools and procedures for safety and security verification and certification for Open-Source Hardware/Software (c.f. Appendix A).

Architectures that provide mitigation, remediation and restoration against physical and software cyber threats ensuring integrity in Data, Software and Systems.

The main expected outcome is a set of solutions to ensuring the protection of personal data in the embedded AI and data-driven digital economy against potential cyber-attacks:

Ensuring cybersecurity and privacy of systems in the Edge to cloud continuum, via efficient automated verification and audits, as well as recovery mechanism (cfr. Chapter 1.4 “System of Systems” and Chapter 2.3 “Architecture and Design: Method and Tools”).

Ensuring performance in AI-driven algorithms (which needs considerable data) while guaranteeing compliance with European privacy standards (e.g., general data protection regulation - GDPR).

Establishing a cybersecurity and privacy-by-design European data strategy to promote data sovereignty.

Establishing Quantum-Safe Cryptography Modules.

Establishing a transparency security approach toward Open-Source Hardware/Software Architecture (c.f. Appendix A)

The main expected outcome is to ensure compatibility, adequacy and coherence in the joint use of the promoted security solutions, and the safety levels required by the system or its components:

Maintaining the nominal or degraded system safe level behaviour when the system’s security is breached or there are accidental failures.

Guaranteeing information properties under cyber-attacks and adversarial AI (quality, coherence, integrity, reliability, etc.).

Ensuring safety, security and privacy of embedded intelligence (c.f. Chapter 1.3 “Embedded Software and beyond”).

Guaranteeing a system’s coherence among different heterogeneous requirements (i.e. secure protocols, safety levels, computational level needed by the promoted mechanisms) and different applied solutions (i.e. solutions for integrity, confidentiality, security, safety) in different phases (i.e. design, operation, maintenance, repair and recovery).

For safety-critical applications, the open-source software (for instance: Virtual Prototypes, compilers and linkers, debuggers, programmers, integrated development environments, operating systems, software development kits and board support packages) must be qualified regarding functional safety and security standards in order to offer a possibility to create transparent, auditable processes for ensuring safety and security (c.f. Appendix A and Chapter 3.1 “Mobility”).

Assess complex System-on-Chip implementations and a Chiplet approach assembling functional circuit blocs with different functions (e.g.: processor, accelerator, memories, interfaces, etc.) regarding security functionalities, focusing on scalability, modularity as well as Edge paradigm (c.f. Appendix A).

Developing rigorous methodology supported by evidence to prove that a system is secure and safe, thus achieving a greater level of transparency without compromising information and trustworthiness.

Evaluating the environmental impact of the implemented safety and security solutions (the green chapter connection).

Safety has always been a key concept at the core of human civilisation. Throughout history, its definition, as well as techniques to provide it, has evolved significantly. In the medical application domain, for example, we have witnessed a transformation from safe protocols to automatic medication machines, such as insulin pumps and respiratory automation, which have integrated safety provisions. Today, we can build a range of different high-integrity systems, such as nuclear power plants, aircraft and autonomous metro lines. The safety of such systems is essentially based on a combination of key factors, including: (i) determinism (the system’s nominal behaviour is always the same under the same conditions); (ii) expertise and continuous training of involved personnel; (iii) deep understanding of nominal and degraded behaviours of the system; (iv) certification/qualification; and (v) clear liability and responsibility chains in the case of accidents.

This context has been considerably challenged by the predominant use of AI-based tools, techniques and methods. A capital example is the generative AI, which is forcefully and naturally making its way into the digitalization of ubiquitous electronic components and systems.

Techniques based on Machine Learning, generative AI and more generally AI are used mainly in two ways: embedded in ECS and as a tool for carrying out safety analysis.

Much has been written about the limits of traditional safety techniques, which need to be extended and/or embedded in new overall safety-case arguments, whenever ECS embeds IA. In comparing, much less has been said about the use of AI to perform safety analysis in compliance with the regulations.

To govern this contest, a couple of years ago Europe published AI act. The international standardization group ISO/IEC JTC 1 is hardly working and publishing a set of standards, which are character to being domain independent applications. Even in the nuclear domain, certainly among the most restrictive and conservative ones, the related industrial community is investigating, not without a live internal debate, on how to use of AI-based techniques, identify the limits and study their impacts on safety (see e.g., the activities and works of IEC TC 45 SC 45A and the International Atomic Energy Agency).

This major challenge is devoted to understand and develop innovations, which are required to increase the safety and resilience of systems in compliance with AIact and other related standards, by tackling key-focus areas involving cross-cutting considerations such as legal concerns and user abilities, and to ensure safety-related properties under a chiplet-based approach (c.f. Appendix A, introduction).

The vision points to the development of safe and resilient autonomous systems in dynamic environments, with a continuous chain-of-trust from the hardware level up to the applications that is involved in the accomplishment of the system’s mission, including AI. Our vision takes into account physical limitations (battery capacity, quality of sensors used in the system, hardware processing power needed for autonomous navigation features, etc.), interoperability (that could be brought e.g. open source hardware c.f. appendix A), and considers optimizing the energy usage and system resources of safety-related features to support sustainability of future systems. Civilian applications of (semi-) autonomous mobile systems are increasing significantly.

This trend represents a great opportunity for European economic growth. However, unlike traditional high-integrity systems, the hypothesis that only expert operators can manipulate the final product undermines the large-scale adoption of the new generation of autonomous systems.

Civilian applications thus inherently entail safety, and in the case of an accident or damage (for example, in uploading a piece of software in an AI system) liability should be clearly traceable, as well as the certification/qualification of AI systems.

In addition to the key focus areas below, the challenges cited in Chapter 2.3 on Architecture and Design: Methods and Tools are also highly relevant for this topic, and on Chapter 1.3 on Embedded Software and beyond.

The expected outcome is systems that are resilient under physical constraints and are able to dynamically adapt their behaviour in dynamic environments:

Responding to uncertain information based on digital twin technology, run-time adaption and redeployment based on simulations and sensor fusion.

Automatic prompt self-adaptability at low latency to dynamic and heterogeneous environments.

Architectures, including but not limited to the RISC-V ones (cfr. appendix A) that support distribution, modularity and fault containment units to isolate faults, possibly with run-time component verification.

Use of AI in the design process – e.g. using ML to learn fault injection parameters and test priorities for test execution optimization.

Develop explainable AI models for human interaction, systems interaction and certification.

Resource management of all systems’ components to accomplish the mission system in a safe and resilient way. Consider to minimize the energy usage and system resources of safety-related features to support sustainability of future cyber-physical systems.

Identify and address transparency and safety-related issues introduced by AI applications.

Support for dependable dynamic configuration and adaptation/maintenance to help cope with components that appear and disappear, as ECS devices to connect/disconnect, and communication links that are established/released depending on the actual availability of network connectivity (including, for example, patching) to adapt to security countermeasures.

Concepts for SoS integration, including legacy system integration.

The expected outcome is clear traceability of liability during integration and in the case of an accident:

Having explicit workflows for automated and continuous layered certification/qualification, both when designing the system and for checking certification/qualification during run-time or dynamic safety contracts, to ensure continuing trust in dynamic adaptive systems under uncertain and/or dynamic environments.

Concepts and principles, such as contract-based co-design methodologies, and consistency management techniques in multi-domain collaborations for trustable integration.

Certificates of extensive testing, new code coverage metrics (e.g. derived from mutation testing), and formal methods providing guaranteed trustworthiness.

Ensuring trustworthy electronics, including trustworthy design IPs (e.g. source code, documentation, verification suites) developed according to auditable and certifiable development processes, which give high verification and certification assurance (safety and/or security) for these IPs (cfr. appendix A).

The expected outcome is to ensure safety for the human and environment during the nominal and degraded operations in the working environment (cf. Major Challenge 5 below):

Understanding the nominal and degraded behaviour of a system, with/without AI functionality.

Minimising the risk of human or machine failures during the operating phases.

Ensuring that the human can safely interface with machine in complex systems and SoS, and also that the machine can prevent unsafe operations.

New self-learning safety methods to ensure safety system operations in complex systems.

Ensuring safety in machine-to-machine interaction.

This ECS SRIA roadmap aligns societal needs and challenges to the R & D & I for electronic components. The societal benefits thereby motivate the foundational and cross-sectional technologies as well as the concrete applications in the research agenda. Thereby, many technological innovations occur on a subsystem level that are not directly linked to societal benefits themselves until assembled and arranged into larger systems. Such larger systems then most of the time require human users and beneficiary to utilize them and thereby achieve the intended societal benefits. Thereby, it is common that during the subsystem development human users and beneficiaries stay mostly invisible. Only once subsystems are assembled and put to an operational system, the interactions with a human user become apparent. At this point however, it is often too late to make substantial changes to the technological subsystems and partial or complete failure to reach market acceptance and intended societal benefits can result. To avoid such expensive and resource intensive failures, Human Systems Integration (HSI) efforts attempt to accompany technological maturation that is often measured as Technological Readiness Levels (TRL) with the maturation of Human Readiness Levels (HRL). Failures to achieve high HRL beside high TRLs have been demonstrated in various domains such as military, space travel, and aviation. Therefore, HSI efforts to achieve high HRLs need to be appropriately planned, prepared, and coordinated as part of technological innovation cycles. As this is currently only rarely done in most industrial R&D activities, this Chapter describes the HSI challenges and outlines a vision to address them.

There are three high-level HSI challenges along ECS-based products:

The first challenge is to design products that are acceptable, trustworthy, and therefore highly likely to be used sustainably to achieve the expected individual, organizational, or societal benefits. Thereby, the overall vision for the practical use of a product by real users within their context is currently often unknown at the time of the technological specification of the product. Instead, the technological capabilities available in many current innovation environments are assembled to demonstrate merely technological capabilities but not operational use. This is often mistakenly called “use case” as it means “use to demonstrate the product” not “realistic use of the product by real users in realistic environments”. Thereby, sufficiently detailed operational knowledge of the environmental, organizational, and user characteristics is often not available and cannot be integrated into technology development. Therefore, the conception of accepted and trusted, and sustainably used technologies is often the result of trial-and-error, rather than strategically planned development efforts.

The second challenge consists of currently prevalent silos of excellence where experts work within their established domain without much motivation, ability or interest to requirements that seem external to their domain. Instead, success is often seen as promoting the own area of expertise. This forms effective resistance against a holistic design of a system instead of subcomponent optimization and makes it difficult to design products for accepted, trusted, and sustained usage. For example, increasingly complex and smart products require often intricate user interactions and understanding that is beyond simpler “non-smart” products. Thereby, the developing engineers often do not know the concrete usage conditions of the to-be-developed system or constraints of their users and are therefore unable to make appropriate architecture decisions. For example, drivers and workers generally do not like to purely monitor or supervise automated functions, while losing active participation. This is especially critical when humans have to suddenly jump back into action and take control when unexpected conditions require them to do so. Therefore, aligning the automation capabilities with the human tasks that are feasible for users to perform and to match their knowledge and expectable responsibilities, are becoming paramount to bring a product successfully to the market. However, currently established silos of engineering excellence in organizations are difficult to penetrate and therefore resist such as external perceived requirements.

Thirdly, continuous product updates and maintenance are creating dynamically changing products that can be challenging for user acceptance, trust, and sustained usage. Frequent and increasingly automated software updates have become commonplace to achieve sufficiently high security levels and to enable the latest software capability sets as well as allow self-learning algorithms to adapt to user preferences, usage history, and environmental changes. However, such changes can be confusing to users if they come unannounced, or are difficult to understand. Also, the incorrect usage that may result from this may lead to additional security and acceptance risks. Therefore, the product maintenance and update cycles need to be appropriately designed within the whole product lifecycle to ensure maximum user acceptance and include sufficient information on the side of the users. Here HSI extends beyond initial design and fielding of products.

The vision and expected outcome is that these three HSI challenges can be addressed by appropriately orchestrating the assessments of needs, constraints, and abilities of the human users, and use conditions with the design and engineering of products as well as their lifetime support phases. Specifically, this HSI vision can be formulated around three cornerstones:

Vision cornerstone 1: conceiving systems and their missions, based on a detailed analysis of acceptance and usage criteria during the early assessment of the usage context. This specifically entails the assessment of user needs and constraints within their context of use and the translation of this information into functional and technical requirements to effectively inform system design and development. Such information is currently not readily available to system architects, as such knowledge is currently either hidden or not assessed at the time when it is needed to make an impact during system conception. Instead, such assessments require specific efforts using the expertise of social scientists such as sociologists, psychologists, and human factors researchers who have also familiarity or training in engineering processes. As part of this cornerstone, assessments are conducted that describe the user population and the usage situation including criticality, responsibilities, environment, required tasks and time constraints. Also, the organizational conditions and processes within which the users are expected to use the system play an important role that should impact design decisions, for example to determine appropriate explainability methods. This assembled information is shaping the system architecture decisions and is formulated as use cases, scenarios, and functional and technical requirements.

Vision cornerstone 2: to translate the foundational requirements from cornerstone 1 into an orchestrated system mission and development plan using a holistic design process. Multifaceted developer communities thereby work together to achieve acceptable, safe, and trustworthy products. Thereby, the product is not designed and developed in isolation but within actively explored contextual infrastructures to bring the development and design communities close to the use environment and conditions of the product. Considering this larger contextual field in the design of products requires advanced R&D approaches and methodologies, to pull together the various fields of expertise and allow mutual fertilization. This requires sufficiently large, multi-disciplinary research environments for active collaboration and enablement of a sufficient intermixture between experts and innovation approaches. This also requires virtual tool sets for collaboration, data sharing, and solution generation.

Vision cornerstone 3: detailed knowledge about the user and use conditions are also pertinent to appropriately plan and design the continuous adaptations and updates of products during the lifecycle. Converging user knowledge and expectations will allow more standardized update policies. This will be addressed by bringing the end-users, workers, and operators toward achieving the digital literacy with a chance to enable the intended societal benefits. The formation of appropriate national and international training and educational curricula will work toward shaping users with sufficiently converging understanding of new technology principles and expectations as well as knowledge about responsibilities and common failure modes to facilitate sustained and positively perceived interactions.

Within these cornerstones, the vision is to intermingle the multi-disciplinary areas of knowledge, expertise, and capabilities within sufficiently inter-disciplinary research and development environments where experts can interact with stakeholders to jointly design, implement, and test novel products. Sufficiently integrated simulation and modeling that includes human behavioral representations are established to link the various tasks. The intermingling starts with user needs and contextual assessments that are documented and formalized sufficiently to stay available during the development process. Specifically, the skills and competences are formally recorded and made available for requirements generation.

Figure 2.4.3 - Human Systems Integration in the ECS SRIA

Systematize methods for user, context, and environment assessments and sharing of information for user-requirement generation. Such methods are necessary to allow user centered methods to achieve an impact on overall product design.

Develop simulation and modeling methods for the early integration of Humans and Technologies. The virtual methods link early assessments, holistic design activities, and lifelong product updates and bring facilitate convergence among researchers, developers, and stakeholders.

Establish multi-disciplinary research and development centers and sandboxes. Interdisciplinary research and development centers allow for the intermingling of experts and stakeholders for cross-domain coordinated products and life-long product support.

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Definition of softwarisation and virtualisation standards, not only in networking but in other applications such as automation and transport | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| luating the impact of the contextualisation environment on the system’s required levels of safety and security | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vital societal functions: services and functions for maintaining the functioning of a society. Societal functions in general: various services and functions, public and private, for the benefit of a population and the functioning of society.↩